August, 2014 – Artifact of the Month

Back to PAF Home

Back to Artifact of the Month Index

Back to Burial Places Forum

Cemetery Stones with Many Lives

Archaeological field record photograph (McVarish, et. al. 2005; (Inset) Fountain in Franklin Square, Philadelphia, by J. Childs & Company, 1851 [from McVarish et. al., 2005:6])

This month’s artifact is a collection of cemetery headstones that have lived ‘many lives’ themselves. Originally created as mortuary items these headstones (also known as tombstones, gravestones, stele or markers) date to the 18th and early-19th century. They were erected in what came to be known as Franklin Square (originally called North East Publick Square). After a time as burial markers, these artifacts served a second function becoming part of the City of Philadelphia’s landscape history. Today, archaeologists have given them a third use as an important historical resource for researching genealogy.

Origin History

Franklin Square forms the northeast square in the plan for the city of Philadelphia created for William Penn. Overtime, the square has had many uses. Early on, portions were rented for a grazing ground and for a potter’s field and stranger’s burial ground. At another time the square held a powder magazine, and later, a horse and cattle market (see McVarish et. al. 2005, Yamin et. al. 2007 and Yamin 2008). One early use, lasting close to a hundred years, was as part of the *First Reformed Church of Philadelphia’s burial ground. Founded in 1727 by German and German-Swiss immigrants, the church bought land for its burial ground in the vicinity of the square and later rented land in the square when their community’s needs expanded. As many as 3100 burials may have taken place in the area during the period of this use by the church (Yamin 2008:191). [*Founded as the German Reformed Church of Philadelphia and known today as the Old First Reformed United Church of Christ.]

Image of an original Deed in Trust regarding the church burial ground, signed in 1763, as depicted in Old First Reformed Church of Philadelphia Christian Schneÿder’s Story by N. Patricia Armstrong, who references the Archives of Old First Reformed Church of Philadelphia for the image source.

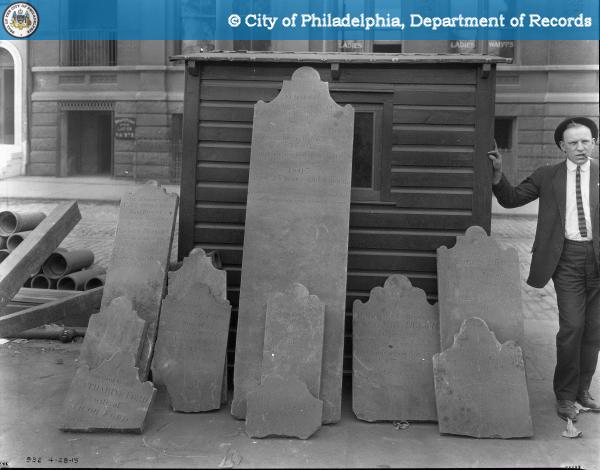

Sometime after 1819, the city rescinded the lease of its land to the church and burials by the church in the square were discontinued. The city allowed for the extant First Reformed grave stones to be “laid flat on top of the burials and the ground (was) graded above them” (McVarish et.al., 2005: 14; Appendix A:4). As with other (quite common) incidents of burial ground termination, be it on a city property or on burial grounds that become city land, some burials may have been relocated at this time — but many were not. (Other local examples of this happening include Lafeyette Cemetery in South Philadelphia, the Germantown Potter’s field or Stranger’s Burial Ground on Queens Lane, the Bishop’s Ground cemetery on Washington Avenue, the AME Church Burial Ground at Wiccacoe Park, and the Second Presbyterian Burial Ground at what is now the location of the National Constitution Center, etc.) Information from the City Archives indicates that many of the cemetery stones from this burial ground, and the burials they marked, were impacted during a 1915 sewer line construction, and again, with much less impact, during a smaller 1976 sewer project (McVarish 2005).

City Archives Photo, 4/28/1915, showing gravestones uncovered during a 1915 sewer project in Franklin Square. (City Archives Photo Collection, File 638, from McVarish et. al. 2005:Figure 8).

Artifacts with a Second Life: Cemetery Stones As Landscape Features

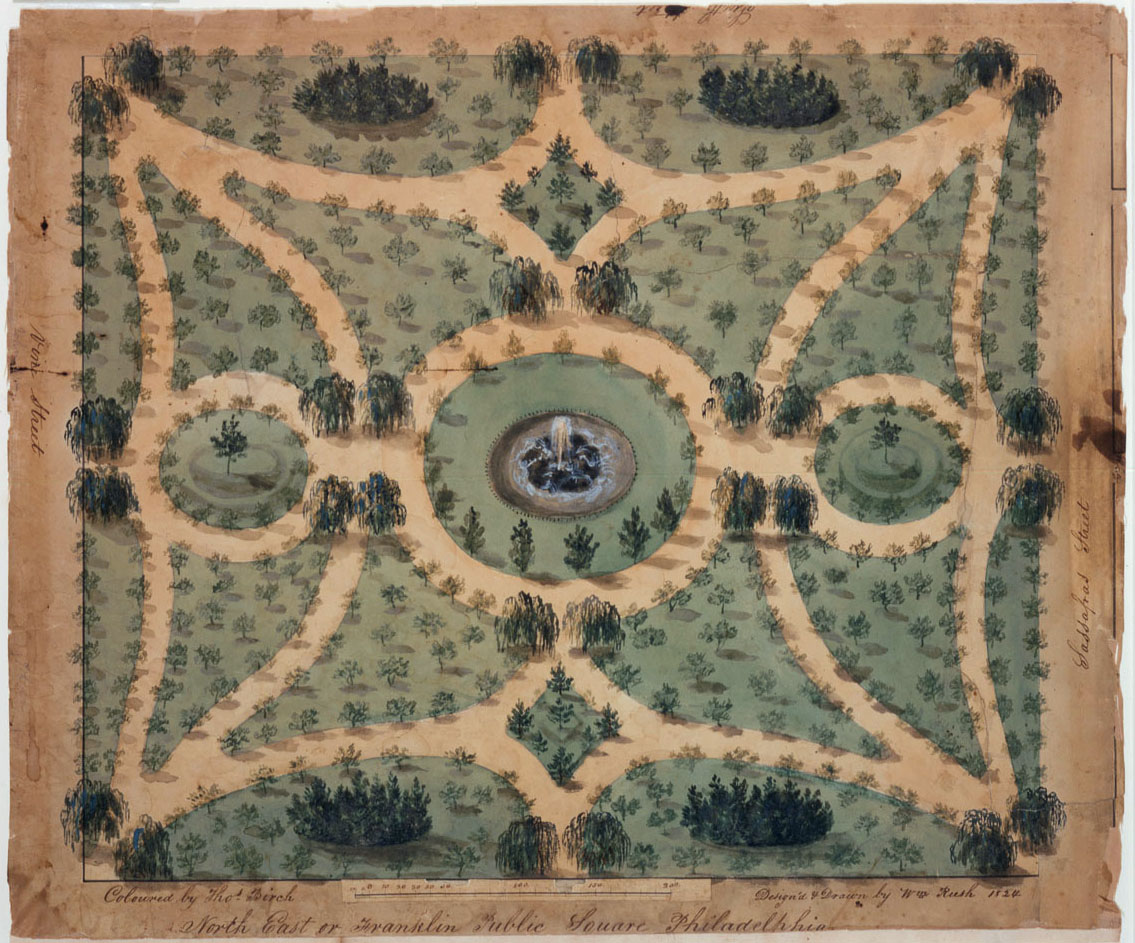

By 1837, Franklin Square was an urban park. The plan for the landscaping of Franklin Square with a central fountain and geometrical walks existed as early as 1824. Created by William Rush (who also designed Rittenhouse Square), the plan was “similar to the formal Renaissance inspired style fashionable in the eighteenth and early nineteenth centuries, but the prevalence of curved lines suggests the naturalistic style that was to become popular in the middle of the nineteenth century” (McVarish et al. 2005:15). Archaeological research in the square in 2005 (McVarish et al.) and 2007 (Yamin et. al.) recovered information about the creation of the park’s 19th century landscaping: In the northeast corner of the park, First Reformed Church cemetery stones were used/reused in the construction of several graceful, curvilinear, walkways.

Archaeological Research

During the spring of 2006, Once Upon A Nation [Historic Philadelphia], in conjunction with Fairmount Park and the City of Philadelphia, began the rehabilitation of Franklin Square to transform the square into a fairground that would serve both tourists and the city’s inhabitants. In preparation for this renovation, two archeological sensitivity reports were prepared by John Milner Associates, Inc. (McVarish et. al. 2005; Yamin et. al. 2007). The background studies undertaken for this provided a history of the First Reformed Church burial ground that was known to exist on the square between 1741 and 1836. The archeological monitoring that was done revealed that intact burials remained present in a portion of Franklin Square in addition to other historical remains including “a cobble surface possibly associated with an early nineteenth-century cattle yard, two walls that may relate to a structure south of a powder magazine, gravel fills associated with nineteenth and early twentieth-century walkways, and a distinctive red gravel fill that was the surface of a walkway that used headstones set on their sides for curbing” (Yamin et. al. 2007:Abstract). Artifacts excavated from the fill associated with this walkway dated its construction to after 1830, the time period during which the City regained control of the square and landscaped it as a park (Yamin et. al. 2007:Abstract,59).

Archaeological research discovered headstones positioned standing on their side, end to end, creating a curb for a curvilinear walkway. (Figure 10, Plate 41 abstracted from Yamin et. al. 2007:38)

These tombstones were no longer associated with human remains and were not in their original burial memorial positions. In other cases, headstones were found repositioned so that “their inscribed sides were intentionally placed against a yellowish brown subsoil fill” (Yamin et. al. 2007:44). When considered together, these repositioned headstones all appeared to be part of a curvilinear walkway. The stones were used as curbing along a sand and gravel walkway in an architecturally designed, Victorian-era park (Yamin et. al., 2007;59).

History Recycled

Surprising as it may be, informal and formal recycling of gravestones has long occurred both in the US and in Europe. Tombstones have been used as building foundation material, for pavers, for building jetties and rain gutters — and for new headstones. In some cases the stones are un-sanctified (taken from still consecrated soil). This type of usage involves vandalism, a lack of judgement and or concern (such as in a recent case involving Arlington Cemetery)– and, in other instances, an effort, perhaps, to erase memory, as in the case of matzevot (Jewish gravestones) looted and otherwise appropriated (“quarried”) from Jewish cemeteries in Poland since World War II.

However, in many cases, gravestone recycling occurs more pragmatically with stones whose associations are no longer part of public memory. This is due to the fact that the stones have existed through a deep passage of time — much longer than 75 years, with 3 or 4 generations having passed. This reuse in formal contexts (when undertaken by an institution of authority) is not uncommon and is, at the time of its occurrence, generally considered a practical action.

Such is the presumed case with the building of the 19th century landscape of Franklin Square which allowed city dwellers “to experience and enjoy the beauty of nature”. (See post by Joshua Lisowski February 25, 2014, the Encyclopedia of Greater Philadelphia). Landscape gardening and urban planning merged during this period to create an American park tradition that was ‘public green space’ reshaping urban public space. The creation of a picturesque landscape was thought to have “a transformative impact on public health and moral behavior” (Layton-Jones 2008). In this transformation, a cemetery evolved into a (manufactured) natural oasis in the burgeoning, industrializing, city.

It is interesting to note that this cemetery space was becoming a bucolic public place at the same time that romantic perceptions of nature were shaping burial ground practices in what is known as the “rural cemetery movement”. The formation of Laurel Hill Cemetery in Philadelphia in 1836 is a prime example of this new tradition of picturesque and romantic memorial landscapes that came to be looked upon, themselves, as public parks. Franklin Square is, in essence, an early example of the historic relationship of cemetery and municipal park planning in America. (For discussion of this relationship see, among others, the National Register Bulletin Guidelines for Registering Cemeteries and Burial Places; Schuyler 2006)

. Image from Philadelphia and its Environs, and the Railroad Scenery of Pennsylvania.” Published in 1875 by J. B. Lippincott and Co., Falvey Memorial Library, Villanova University.

Today: Contributing Anew to Family Genealogy

Upon their discovery in 2005 and 2007, the archaeological team recorded the gravestones found in Franklin Square as material culture ‘artifacts’. As such, they were photographed, mapped, and — importantly — their inscriptions were transcribed. These actions represented ‘standard practice’ in archaeological field research for the recording of discovered artifactual remains but it was also a fortuitous action for others who study and preserve graveyards (see for example, the Association of Gravestone Studies) and for those involved in what is, now, the number one avocational interest – family genealogy (see among others, Genealoger, Billion Graves).

Tombstones are artifacts that bear literal information about a deceased — name and date of death, if known — as well as more ephemeral, cultural information that is not otherwise guaranteed to be found in another form of written record. Cemetery records will usually indicate who purchased the burial plot, who was buried there, and the date of burial. They may also contain the cause of death, the funeral home, the parents’ names, and the relationship of the plot owner. However while the memorial stones themselves are ‘texts’ speaking about the dead they are also material culture evidence left by the living. The stones can hold information that others found important enough about a deceased to have it memorialized. This can include a place of birth, kinship information that differs from a legal relationship, and sometimes guild and religious associations or significant events related to the life or death of the individual (e.g., “survivor of ‘X’ shipwreck”, “Settler Family” indicating a community founder status that the living continue to experience).

Karen Lind Brauer, a researcher who brings historical archaeology methods into genealogical studies, points out that the congregants from the First Reformed Church were immigrants from Europe and that while the church might have a record of baptisms, marriages and deaths that occurred in Philadelphia it is less likely that the deceased European-based birth information is recorded in any Church documents: “This is an good example of where archaeological research may inform genealogical research by perhaps providing the town name that the settler was born in, who it was that was buried together, and other incidental information left out of formal church records” (pers. com. to author, July 29th).

This kind of information, deeply sought after by descendants and others researching family history, now exists for several early congregants of the First Reformed Church. The archaeologists have provided this data for poserity in their reports. The stones themselves were left in place where the archaeologists discovered them or, if disturbed by the Fairground development, were reburied elsewhere in Franklin Square.

Below are transcribed inscriptions from some of the gravestones found at Franklin Square during the 2005 and 2007 archaeological studies.

“In Memory of/ MARY, the Wife

of/ LEWIS KARCHER/ Born the

2th day September/ 1738 died the

3th day of August 1797/ Aged 58

Years an…/ What is Man that

the…/ And the for…” (Yamin et. al. 2007:Appendix A, Burial #39)

Leibe nach/

JOHANNES GAMBER/ Gebohren

im Jahr 1696 den 6 January, und

gestorben den 7r October/ 1762;

Seines Alters 66 Jahr 9 Monat/

(skip line)/ An diesen Stein Kauft

du noch Lebend feht Wie alles

Fliesch Zu Lerzr doch mus er geht/

Und ob du gleich Mathusalems

Alder…/ …st es doch im Gr…

Here rests the body of

Johannes Gamber

Born in the year 1696 on

the 6th

Of January, and died on

the 7th of October

1762; his age 66 years 9

months

… future survivors

How all flesh in the end

must pass away

And … same …

… 6 …

… also the Everlasting ..(Yamin et. al. 2007:Appendix A, Burial #53)

Hier/ Ruher in ihrem Ehl…fer/

die von/ LEONHART

MELCHIOR/ Und seiner

Ehelichen frauen/ ANNA MARIA/

…mder als: Anna Maria, war…

[geboh]ren den 29 October.

Here

Rests in her …

Who from

Leonard Melchior

And his legal wife

Anna Maria

…..

… Anna Maria was …

[Born] on the 29th of

October …

[Died] on the 28th of

April [1748]

[Age] 2 years 6 [months]

I rest here by my husband’s side,

Who short time before me was a prey

of illness

In those days of horror.

To me immediately after his going

away

Death seemed through harsh grieving

As only a sinner’s bed.

He (Death) waved me with

seriousness to the grave.

Thus I with my pilgrim’s staff

Refused his solemn waving.

I looked upon the end of the journey

Gave my spirit in Jesus’s hands,

And Jesus rewarded me with the

crown.

Trans. Barbara Blomeier, Bielefeld,

Germany

And Anna M[argaret]

Born …

… [died…] the 28th of

July, 17[48]

Aged 1 year 2 days../ …

staub der 28 April 1…/ 2 Jahr, 6

Mo[nat]/Und Anna M[aria]…/

gebohren den 28 July 174…/ alt 1

Jahr 2 Tag (Yamin et. al 2007:Appendix B, Burial #1)

———–

This Artifact of the Month write up was contributed by Patrice L. Jeppson, Ph.D., August 4, 2014

________________________________________________________________

For more information:

An Archaeological Sensitivity Study of Franklin Square Philadelphia

Prepared for

Once Upon a Nation

By

Douglas C. McVarish

Rebecca Yamin, Ph.D.

Daniel G. Roberts, RPA

John Milner Associates, Inc.

2005

“LEAVING NO STONE UNTURNED”: ARCHEOLOGICAL MONITORING AND THE TRANSFORMATION OF FRANKLIN SQUARE PHILADELPHIA, PENNSYLVANIA

Prepared for

Once Upon a Nation

by

Rebecca Yamin, Ph.D.

Alexander B. Bartlett

Nancy Donohue

With a contribution by

Arthur Washburn, Ph.D

For more on those buried in the German Reformed Burying Ground, see Section 4.0, The People Buried in Franklin Square, by Nancy Donohue, pages 41, in Yamin et. al., 2007.

Chapter 10, Digging in the City of Brotherly Love: Stories from Philadelphia Archaeology

By Rebecca Yamin. Yale University Press, 2008.

Constitution Center Site Bears Buried Links To The City’s Past

By Charlene Mires, June 26, 2000. Philly.com

Independence Mall Dig Uncovers Colonial Graves Burial Plots For 15 Were Discovered. The Excavation Is Being Done To Prepare For The Constitution Center.

By Saba Bireda, INQUIRER STAFF WRITER. June 21, 2000

Tombstones for jetties CNN Video 1:38

While fishing, a father and son discover more than fish: tombstones. Turns out, the city put them there. September 6, 2008

Recycled gravestone sparks family anger

Wales On-line, Nov. 8, 2012

Headstone Remnants In Buena Vista Park

“Buena Vista Park” by Jeanne Alexandar, SFHR, San Francisco Neighborhood Parks Report.

Poland’s Undead Gravestones. Photographer Łukasz Baksik hunts repurposed matzevot, burial markers turned cornerstones and cobbles.

Tablet, a New Read on Jewish Life. April 17, 2013.

Arlington Cemetery officials knew about discarded tombstones found in stream

By Christian Davenport, Washington Post Staff Writer, Wednesday, June 23, 2010

Stage Sets for Society: Nineteenth-Century Public Parks. Review of Heath Massey Schenker. Melodramatic Landscapes: Urban Parks in the Nineteenth Century. Charlottesville: University of Virginia Press, 2009., for H-Urban, H-Net Reviews by Katy Layton-Jones (September, 2011).

National Register Bulletin, Guidelines for Evaluating and Registering Cemeteries and Burial Places, Section II, BURIAL CUSTOMS AND CEMETERIES IN AMERICAN HISTORY. US. Department of the Interior, National Park Service.

The New Urban Landscape: The Redefinition of City Form in Nineteenth Century America

by David Schuyler. 1986

German Reformed Church; Old First Reformed United Church of Christ history

_______

Back to Artifact of the Month Index

by admin