March 2018 – Artifact of the Month

To PAF HOME

To Artifact of the Month Index

~~~

Cats in the Past:

Archaeological evidence of feline epidemic disease in early America

Highly infectious diseases have always plagued (pun intended) densely populated urban areas. That holds true for diseases afflicting wild as well as domestic animals that live alongside humans in cities. The archaeological record of Philadelphia is beginning to reveal some of this animal disease history.

A less celebratory ‘Philadelphia First‘

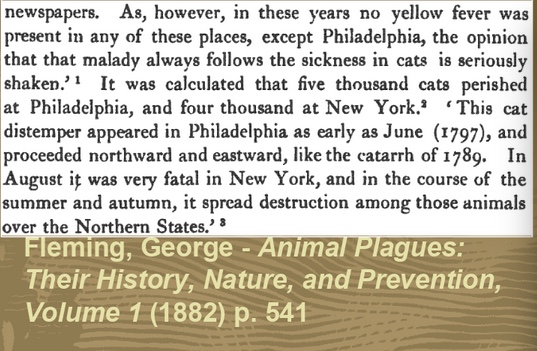

The first recorded feline distemper epidemic in the US is reported in documents as beginning in Philadelphia in 1797. Five thousand cats are reported to have died in the city during the outbreak. (See abstracted quote from G. Fleming below). This would have been just four years after the worst human epidemic in U.S. history struck Philadelphia – the spread of Yellow Fever that left more than 5000 people dead in just three months in 1793.

At the time of this feline, or cat, distemper epidemic, the U.S. was still a very young country. The Presidency had recently passed from George Washington to John Adams, who continued to govern from Philadelphia during the construction of a new capital city (Washington DC). Philadelphia’s population had grown to 50,000 people, and the city’s port was the busiest in North America. The City’s human residents – and their cats – shared a dense urban landscape with, among other domesticated animals, horses, dogs, chickens, pigs, sheep, goats, and cows. Wild and captured rodents and bird species lived with and around them. When the feline distemper struck, tens of thousands of cats died within a few years as the disease spread north and south along the eastern seaboard.

What is Feline Distemper?

Feline Distemper @ Wikipedia

Feline panleukopenia virus (FPV), also known as feline infectious enteritis, feline parvoviral enteritis, feline distemper, feline ataxia, or cat plague, is a viral infection affecting cats, both domesticated and wild feline species…. Once contracted, it is highly contagious and can be fatal to the affected cat. The name panleukopenia comes from the low white blood cell count (leucocytes) exhibited by affected animals….Feline panleukopenia requires aggressive treatment if the cat is to survive, as this disease can kill cats in less than 24 hours. ….Protection is offered by commercial feline FVRCP vaccines….

Studying Animal Remains From Archaeology Sites in Philadelphia

The study of animal bones in archaeology is known as faunal analysis or zooarchaeology. Researchers who specialize in this area are called faunal analysts, archaeozoologists, or zooarchaeologists. Recently, archaeological researchers working on faunal collections from Independence Historical National Park in Philadelphia discovered what are likely the victims of this early feline plague.

The evidence comes from the skeletal remains of several cats excavated by archaeologists more than a decade ago at the site of the National Constitution Center in Independence Park. The skeletal elements represent a number of different individual animals who vary in age from prenatal to elderly. The photograph at the top of this page shows the mandibles, or lower jaws, of these cat skeletons.

The cat bones the archaeologists discovered were excavated from the same soil layer within the archaeology site. This soil layer once comprised part of an early American house lot (Federal period). The property in question was located on the block of Philadelphia that is today demarcated by 5th and 6th streets and Arch and Race Streets. The house lot’s location was excavated prior to the construction of the National Constitution Center museum which stands on the block today.

This collection of cat bones buried more or less together indicates the cats were likely living, and were disposed of in the ground, at around the same time in the years dating to the historically reported epidemic. The faunal specialists concur that the cats were very possibly the victims of this first U.S. feline distemper epidemic.

Such archaeological analysis of faunal evidence can tell us a lot about both the human and animal past:

“….Upwards of a quarter of a million bones [have been recovered by archaeologists excavating in the older portions of the City of Philadelphia]. Some of them show the evidence of cutting and chopping resulting from the butchering, preparation and consumption of the animals [cow, sheep/goat]. But, as we [will] see, not all the bones represent food animals. Companion and working animals are also represented. Just as today, people in colonial and early federal Philadelphia lived with animals as both helpmates and pets. For example, cats might serve as a means of keeping the rodent population under control or simply serve as a friend and a comfort. Bones recovered from archeological sites can tell us much more than what people eat. They can also tell us a great deal about how animals and people interacted in the past and about what their respective lives were like.” (Animal Abuse in the City of Brotherly Love?: Evidence From the National Constitution Center Site, by Jed Levin et., al. 2016.)

Animals as companions – a cat and a pet squirrel – depicted in art of the period. Left image, 1740’s, George Beare (British, active 1738 – 1749), Mrs William Coles; Right image, 1771, John Singleton Copley (American, 1738-1815), Daniel Crommelin Verplanck with Squirrel. For these and other examples go here or here…

Fortunately for today’s cats and their owners, the health of both indoor and outdoor cats can be protected through yearly vaccinations for Feline Distemper (FVRCP).

~~~~

Learn more….

Feline panleukopenia American Veterinary Medical Association web page

1793 Yellow Fever in Philadelphia Epidemic Encyclopedia of Greater Philadelphia

Archaeology at Independence National Historical Park/Independence National Historical Park

National Constitution Center Archaeology Site/Independence National Historical Park

Independence Archaeology Lab/ Independence National Historical Park

Zooarchaeology @ Wikipedia

Information presented in this month’s featured artifact write up (by Patrice L. Jeppson) comes from the talk entitled, “Animal Abuse in the City of Brotherly Love?: Evidence From the National Constitution Center Site”, by Jed Levin, Marie-Lorraine Pipes, Nika Shilobod, and Trevor Totman presented at Explore Philadelphia’s Buried Past: An Archaeology Month Celebration, 2016.

by admin